Photo credit: Michael Durham / Minden Pictures.

All bats in Illinois are obligate insectivores, meaning they only eat insects. Bigger bats eat harder insects like beetles, smaller bats eat smaller species like flies, but almost all of them LOVE moths1,2. There’s a wide range of sizes in moths, from the tiny micromoths with millimeters-wide wingspans to the 6-inch wide cecropia moth, so there’s menu options for bats of all sizes! Moths are a great food source for bats – they’re big, have soft bodies, and are juicy, what’s not to love? Because they’re such a popular option for bats, natural selection has allowed some moths to develop a method for deterring their would-be predators – sonar jamming!

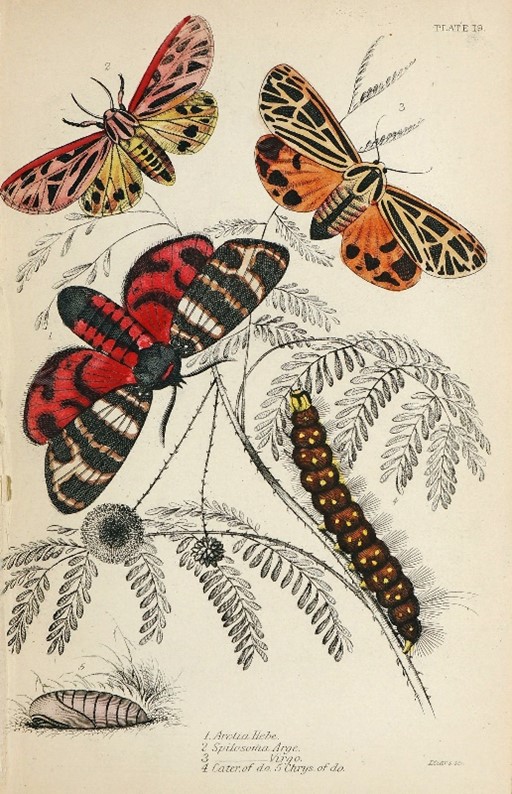

Art by William Home Lizars, 1835

Moths from two families, the tiger moths (Erebidae, Arctiinae) and hawkmoths (Sphingidae), have been documented using sound to deter bats from eating them. But do these moths really jam the bats’ echolocation? A study by Surlykke & Miller in 19853 noted that the moths clicked but it didn’t seem to have an actual effect on the bats’ ability to echolocate, however it did still deter the bats. Instead, they realized that the bats had learned to avoid capturing the moths that click at them because they taste bad! The moths in the study excrete a bitter chemical and the bats had learned that if they hear the moths’ clicks, their food will taste nasty, so they choose not to eat those clicky moths.

The use of signals to communicate that the insect tastes bad is a fairly common defense in moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera.) A famous example of this is a monarch butterfly’s bright color indicating that it’s poisonous and shouldn’t be eaten. Many tiger moths accumulate poisonous or foul-tasting chemicals from plants that they eat as caterpillars, including milkweeds (just like monarchs!), legumes, and plants in the sunflower family. But instead of using colors like monarchs, the moths use sound to tell the bats not to eat them. Some moths may even click like other species, pretending to taste bad to avoid predation without actually having any of the bitter chemicals.

For a while after the 1985 study, scientists thought that the idea of moths actually jamming echolocation was bunk, that they weren’t jamming and instead they were just warning the bats not to eat them. This all changed in 2009 with a study4 involving a tiger moth called Bertholdia trigona and big brown bats. Bertholdia trigona is a strikingly beautiful moth from the southwestern US that has a little trick up its sleeve – it can interrupt a bat’s echolocation!

Photo credit: user VanTruan at Project Noah.

When the Bertholdia moths were put into the bat enclosure, the bats avoided eating them, but the researchers had to prove that the bats’ echolocation was being jammed by the moths instead of it just being another case of the bats knowing to avoid a bad-flavored moth. They showed this in two ways, by testing the moth with naïve bats and by silencing the moths.

The first method utilized bats that hadn’t been previously exposed to the tiger moth to see if the bats were being either startled or warned by the moth. If the moth was just making an unexpected sound to scare the bat, eventually the bat would get used to the noise and catch the moth, and if the moth was warning the bats, they would initially capture the moth, get the unpleasant taste, and then learn to avoid them. Neither was the case, the bats just kept avoiding the moths from the get-go. After this they silenced the moths, and the bats ate them up! Turns out they’re actually quite delicious (to a bat, of course). The moths weren’t startling the bats and they weren’t warning them, either. The moths were actually jamming the bats’ echolocation. Bertholdia trigona is the first evidence of not just a tiger moth, but any animal, using sonar jamming on another animal.

The history of Bertholdia trigona and bats is probably a long one, and it produced one of the most interesting evolutionary arms races in nature, one that gave a moth the ability to “blind” a bat with just some sounds. Aside from tiger moths, there are several other moth families that can perceive bat echolocation calls to avoid predation. Frequent exposure to ultrasonic bat calls has even been recorded to physically change the moth’s physiology over time5. There must be countless unknown interactions like these waiting to be discovered by some young, bright scientists, and I am beyond excited to learn about them as more and more of the mysteries of ecology are uncovered.

Citations:

- Tuttle, N.M., Benson, D.P., Sparks, D.W. (2006). Diet of Myotis sodalis (Indiana Bat) at an urban/rural interface. Northeastern Naturalist 13, 435-442.

- Vaughan, N. (1997). The diets of British bats (Chiroptera). Mammal Review 27, 77-94.

- Surlykke, A., Miller, L.A. (1985). The influence of arctiid moth clicks on bat echolocation; jamming or warning? Journal of Comparative Physiology 156, 831-843. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00610835

- Corcoran, A.J., Barber, J.R., and Conner, W.E. (2009). Tiger moths jam bat sonar. Science 325, 325-327. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1174096

- Cinel, S.D., Talyor, S.J. (2019). Prolonged bat call exposure induces a broad transcriptional response in the male fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda; Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) brain. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00036