There is a common romanticism and nostalgia for classic biological fieldwork—it’s easy to conjure images of Jane Goodall in hiking boots and binoculars patiently crouching in the tall grass waiting for a glimpse into the private lives of wild animals. After a year cooped up inside, I feel called to dust off my hiking boots and return to the field, but things have changed since Dr. Goodall’s days in the field— both in our technological advances and in the state of the wilderness itself.

As biologists pivot and expand their focus to include conservation, conducting wildlife surveys is more important than ever. We cannot protect what we don’t know is there. As much as we can glamorize this vision of field work, classic survey techniques can be time-intensive and expensive. Manually observing animals in nature can be like finding a needle in a haystack; when those animals have well-adapted camouflage, live in difficult terrain or are high flying, emerge only at night, or are so endangered that the likelihood of finding even one is slim, it becomes like finding a needle in a hay-mountain.

Additionally, identifying and differentiating species requires years of training and specialization that isn’t always practical in an era when a myriad of species need expert attention. Finally, some survey techniques can be intrusive and pose a threat to the very individuals we are seeking to protect (including stress of capture or potential for injury).

One solution: environmental DNA also known as eDNA. As organisms move through their environment, trace amounts of genetic material (hair, urine, feces) are left behind in the water, soil, and other organic substances. Anyone from seasoned field technicians to enthusiastic community members can collect these environmental samples and send them off for analysis. eDNA provides a tool kit to cheaply, easily, quickly, and noninvasively survey present wildlife, to make informed conservation decisions (Thomsen and Willerslev 2015).

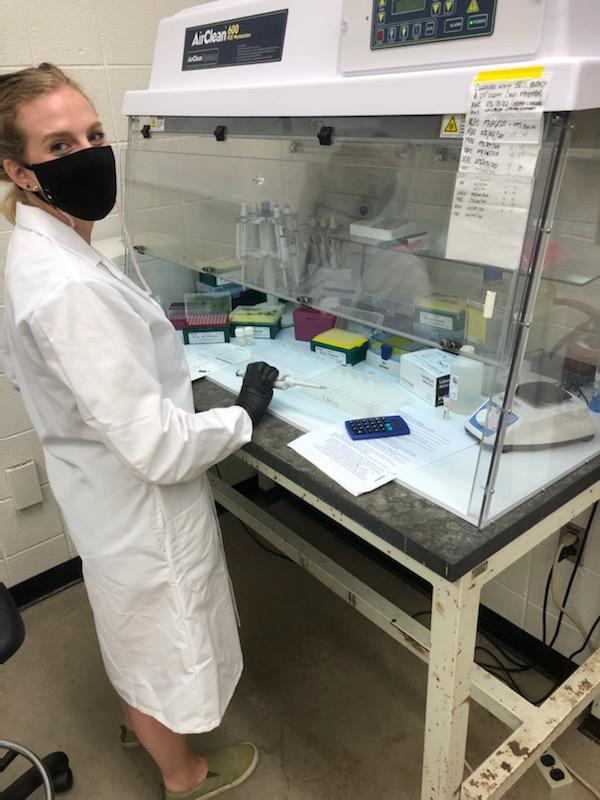

The Illinois Bat Conservation Program (IBCP) is utilizing this cutting-edge technique on several active conservation projects. Guano samples collected from community scientists and professionals around the state are placed into tubes, broken down mechanically and chemically until all that remains is a small amount of DNA. We can use this genetic material in a variety of ways. IBCP frequently uses this DNA from collected guano samples to identify the species using a roost, this reduces the need to capture individuals. Information on the presence of threatened and endangered species is key in making real-time conservation decisions to protect these animals. IBCP is also using this technique to explore what native bats are eating across the state which *spoiler alert* includes invasive species and disease vectors like mosquitos.

The implications of eDNA are exciting and far-reaching. While a lab coat and a pipette might look different than binoculars and hiking boots, eDNA allows researchers and community scientists to come to together for meaningful and efficient conservation of species. We look forward to sharing our results with our community scientists and learning more about the bat distribution across the state.